|

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  | |

|  |  |

|  |  |

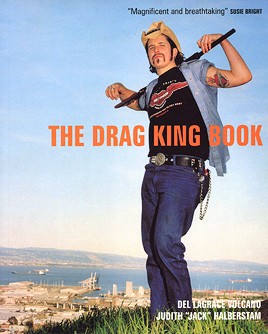

|  |  | There are certainly several ways to introduce Judith Halberstam. She is, to borrow her own description of the intellectual greatness of Stuart Hall and Raymond Williams, rangy. Not only does she work across academic, theoretical, and cultural disciplines, combining funny, stupid, serious, and difficult subjects (while questioning such valorizations), she also has the ability to reach multiple audiences - academic and activist alike. Some may know her from her involvement in the drag king scene - an engagement that has resulted in The Drag King Book (1999), co-authored by the artist Del LaGrace Volcano, presenting kings in San Francisco, New York, and London. She has also appeared in Venus Boyz (2001), a popular documentary film by Gabriel Baur on drag king culture. Others may know Halberstam as an acclaimed Professor of English and, until this year, Director of The Center for Feminist Research at the University of Southern California. Many of her books, especially Female Masculinity (1998) and In a Queer Time and Place (2005), have become central references in academic, cultural, and activist discussions in the US as well as in the Nordic countries. In December 2006 Halberstam visited Malmö in Sweden, giving a talk entitled Notes on Failure, where she presented parts of her forthcoming book. A few months later she was back, this time at The University of Lund where Tiina Rosenberg had invited her and Tuula Juvonen to discuss their thoughts on the subject What's up in queer theory? with a group of international PhD students. After being all ears for three intensive days of lectures, discussions, and lively debates, I sat down with Judith Halberstam to hear what she is up to these days.

JH: I can start by telling you a little bit about the new book which is tentatively called Dude Where's My Theory? It is a humorously title designed to annoy people, but also to reference low culture as a place of a certain kind of knowledge production, as a place where all kinds of ideas are circulated. I reference that funny film Dude Where's My Car?, and that is an important film in my book, but the subtitle will be something like Theorizing Alternatives or Finding Alternatives. |  | |

|  |  |

|  | |

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  | The book is divided into three sections. In the first section I look into critical theory written by people like Louis Althusser, Antonio Gramsci, Hardt and Negri, J.K. Gibson-Graham, Judith Butler and others, and I ask: what has happened with the status of the alternative, or the counter-hegemonic, in critical theory? Critical theory has been very good in the last ten years at pinpointing the problems of the dominant - you know, the notion of “empire” (Hardt and Negri), neo-liberalism, reproduction of capitalist logics, and so on - but I think we have moved away or pulled back from theorizing the alternative. So I want to say: what would the project of theorizing the alternative look like? That is the first section. The second section will be engaged in producing contrary or negative epistemologies. In order to think differently you have to use different categories of knowledge. This section will include, among other things, three topics: stupidity, forgetfulness and failure. The last section of the book returns to the notion of the alternative and it will be on animation. It will be called something like “Animating Revolt”, and I will argue that an interesting archive for looking at alternatives occurs within contemporary animation films and practices. I want to think about the term animation, but also the set of films for children that we call animation, as well as all kinds of other animations. I argue that in the film genre of animation, which is mostly a low genre but a high-tech genre, there are actually some pretty interesting new ways thinking about things. I do not privilege this archive. I just use it as a model or as an example. An easy way, sort of ready at hand - so that we see that the alternative is all around us, rather than being in some arcane set of political practices that are still to be imagined.

MD: I am really interested in your term “contrary epistemologies”. In your talk Notes on Failure in Malmö last year, you discussed the concept of “eccentric knowledge” in relation to this. Can you elaborate on this interest in alternative knowledges? JH: Yes, that is from the middle section of the book. When people want to think differently they actually have to use a) a different archive, and b) different concepts. And it is actually remarkably difficult to think outside of received wisdom, or “common sense”, as Gramsci would call it. We have to be very creative in the way in which we produce both new vocabularies and new structures. We must validate different kinds of concepts and move to different archives, and take seriously what Foucault calls subjugated knowledge. Rather then just saying that subjugated knowledge is knowledge that has been suppressed, and that we must dig deep to find it - we need to understand subjugated knowledge as a form of thinking that has been suppressed. It is a set of topics that have become unimaginable as scholarly topics. Queer is often part of subjugated knowledges simply because it has a hard time presenting itself as relevant knowledge. Who cares, you know, what kind of sex you have, and why and where. There are all these legitimating strategies we have to use to make things seem like a sensible object of knowledge. So another word for eccentric knowledge could be subjugated knowledge. MD: This also points towards your discussion of the distinction between serious and non-serious knowledge production. Your archive is... JH: ...silly! MD: Yes! You put animation figures like SpongeBob and Mumble from Happy Feet side by side with high theorists such as Gramsci and Althusser. JH: That's right. MD: These distinctions of serious/non-serious, high/low knowledge are still present in the academic system today. JH: Yes, and I take the notion of the “silly archive” from Laurent Berlant, who writes about the silly archive. I was speaking with her once, and she went off on a long detailed exposition on South Park, and it was a fabulous conversation and I realized that those kinds of references actually really work for me. Partly because it is so much pleasure involved engaging in texts that you think are fun and funny, and partly because they are just unexpected. Therefore in my formulation they are open texts, in the sense that they do not come with a readymade theory already embedded within them. |  | |

|  |  |

|  | |

|  |  | MD: Today, some of the most interesting voices in queer studies focus on different kinds of knowledge production outside the frames of the traditional academic archive. I think of such books as Ann Cvetkovich's An Archive of Feelings (2003) where she discusses the importance of an oral archive of feelings in telling the stories of lesbian activists in ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) - or art historian Gavin Butt's book Between You and Me (2005) where he uses gossip about artist's sexuality in the US in the 1950s and 1960s as an archive for writing a history of post-war American art. The discussion of the archive can also be related to the current interest in creating cultural canons that we have seen in Denmark and Norway as of lately. I find the political and nationalistic function of the “cultural canons” quite scary. In the US, the concept of the canon was lively discussed and criticized in the aftermath of the publication of The Western Canon (1990) by literature professor Harold Bloom in the 1990s, but notions of “objective” canons are still present today. I think your work is important in this regard, because it focuses on other and alternative archives. JH: Yes, and I think people in general use the word archive as an alternative to canon. So instead of saying “these are the great works, this is the great tradition”, as T.S. Eliot would say, one should recognize that the “great” archive is just one among many. And the great tradition is actually just a tradition, and you can kind of never say that enough in academia, because it seems to be a default mode in the academic world or in the academic consciousness forming the canon. Even today we see this, and it is a very difficult thing to avoid, because you try to make sense of a lot of different text. |  |

|

|  |  |

MD: The criticism of queer theory has since its early days been hammering on the theory's inaccessibility, usually referring to the use of complex deconstructive or psychoanalytical concepts. Especially Judith Butler's rhetoric has been harshly attacked, though this often seems to be by people who do not have cared, or even wanted, to read her work. It seems to me that many queer scholars today try to take on more accessible styles, using other archives, wanting to communicate to a broader public. Even though I think it is important not to position queer theoretical work and queer activism in opposition to each other, it still seems to be a certain antagonism for many people in this regard. Many so-called “difficult” queer theorists have also published quite polemical and accessible books, such as Michael Warner's Trouble with Normal (1999) and more recently Judith Butler's Precarious Life (2004). The Drag King Book (1999) that you did together with Del LaGrace Volcano was also written for a different audience than the academic, I suppose. What are your thoughts on the relation between queer theory and queer activism and practice? JH: Well, a couple of things. One, I have to commend anyone who ends up writing an accessible book. I really do think Butler's recent work shows her range. She made her name as a high theorist, but she is very willing to write other kind of books. I think it is a mark of a certain kind of, not just greatness, but a certain kind of generosity, a desire to communicate and be understood. She has a certain recognition of her position, as somebody who represents something to people, and therefore she wants to communicate it. The second thing is that it is remarkably difficult to write accessibly and maintain complexity. Academics are constantly involved in conversations with other academics, and the desire is to bring those conversations into your work, because that is what, sort of, has produced your thinking. But the minute you bring in an academic dialogue or conversation into a work that is supposed to be accessible, you just lose a huge piece of your audience who are not in academia, who are not having those conversations, and who frankly do not care. So it is very difficult and very schizophrenic because you want to communicate broadly, and I personally find it much easier to do in a talk, than I do in my writing. The Drag King Book, while I am happy that people are able to read it, I also think it is a little bit banal. It was very hard for me to make any real points in that book in the form that I was asked to write in. And then in terms of a queer theory project in general, I do think that communicability is important, and not just having another audience in mind who might not be an academic one, but multiple audiences in mind, is really the key. The models for that kind of intellectual range, that is what I would call it - to be rangy - the model will be someone like Raymond Williams or Stuart Hall. Both Raymond Williams and Stuart Hall among many other people - there are for instance a lot of African-American intellectuals in the US like Robin Kelly, Michael Dyson, bell hooks, and Ruthie Gillmore - who are activists, public intellectuals and academics all in one. They have a really strong sense of commitment to an African-American community that is not well represented in the university; and therefore they have a very strong sense of having to represent people. And I think in queer studies, too. The queer population is far more educated in general. The white, middleclass, queer population is very well educated, and other parts of the queer community are often better educated, if not well educated, than the general population, so it is a different kind of responsibility to a politics than when you find populations who are not at all represented in the university. But I do think that many queer theorists feel that they want their ideas to be taken seriously, and to be in conversation with people who are not on campuses. |  |

|

|  |  |

MD: You write in your latest book In a Queer Time and Place (2005) about the intellectual responsibility in America today... JH: ...yes, to speak up! MD: This responsibility seems related to something you discussed in your lecture Notes on Failure, where you talked about stupidity as a mode of domination. You used George W. Bush as an example of what you called “politics of not-knowing”. Can you elaborate on your thoughts on stupidity? JH: There are a couple of different references here. One is Eve Sedgwick, who has this great anecdote in the introduction to The Epistemology of the Closet (1990) where she tries to show that knowing and unknowing are not in obvious relationships to power. It seems as if knowledge and power are linked, and not knowing and not having power are linked, and in many regimes they are, okay, but she gives the example of President Reagan meeting François Mitterrand in France. Mitterrand is the politician who speaks several languages; Reagan is the politician who is monolingual. So one politician is in more command of knowledge than the other, but because Reagan does not know French, they speak in English. Therefore, the people who are less educated, who have less range, dominate the discourse. Now, that is a pretty interesting analogy for what I am calling domination through the mode of stupidity. You can dominate by not knowing as easily as you can dominate from the position of knowledge. It depends completely on the context. It also depends on how the intellectual has been figured in any given community, and it depends upon class politics and suspicion of intellectual activity, sometimes from working-class people. Bush was able to mobilize this image of himself as a regular guy, despite the fact that he is far from a blue-collar person in the US. In fact, he is Yale educated and blue blood - a political dynasty brat. But through a certain kind of stupidity, he is able to represent himself in fact as “one of the people”. So stupidity, in many many different forms, works against people who are smart. I think that for academics that is just a really good lesson. It is also a different way of reading how stupidity functions in the US: Stupidity does not only function to blot out knowledge; it functions to produce knowledge in a different way. And then the final reference for that would be Avital Ronell, who is a deconstructive philosopher, who has a book called Stupidity (2002), in which she argues that stupidity is not what stands in the way of wisdom, it actually is another way of having wisdom. |  | |

|  |  | MD: The Norwegian left wing author Magnus E. Marsdal recently published the book Frp-koden (2007), where he discusses why and how the extreme right wing came to dominate Norwegian politics, functioning as the new working class party. In his analysis he focuses on how the left wing's contempt for the right wing voters - repeatedly claiming how stupid and uncultivated these people are - have made them an easy catch for the right wing populists who deliberately then have tried to represent the common man's “uncultivated” interests. I guess some of the same disdain for the “stupid” is also evident in Michael Moore's films. His films and books have become popular in Europe, partly I think, through presenting to us a stereotypical image of “the stupid white American man”. But as some have commented, his films might have worked counterproductive in the US, where the right wing easily can play the elitist-card, saying: “we are the party for those the left call the stupid, common man”. JH: Yes, that is exactly how it works! MD: The anti-intellectual atmosphere that has been quite strong in the US public sphere has also been evident in the Nordic countries. How do you think we can counter this anti-intellectualism? JH: That takes me back to my new project, which is about thinking about alternative knowledge in alternative places. What is anti-intellectualism about? Well, it is a fear that a particular class of people who have better access to education and to institutions of education, that those people will simply rule in a world where intellectualism is the currency. So anti-intellectualism can be class-based, it can be a critique of the privilege of education, and it should be taken seriously as something other than just rampant stupidity and ignorance. This is why you have to not be too suspicious of the popular. So for me, I then go to a popular archive and say, well, what are these mass-cultural texts that actually do appeal, do circulate, and do have sort of complex forms, and do contain different kind messages? Can we pull different kinds of intellectual practice from this material that many, many people actually are familiar with? It is an old argument in popular culture studies that to be suspicious of the popular is an intellectual arrogance on the part of academics, and simply locks academics into an eternal struggle with an anti-intellectual populace, who fear that the academics are sneering at them, when in fact, the academics are sneering at them! And they sneer at them by saying that “this film is stupid!” “Don't you know who Jackson Pollock is?” “Haven't you listened to Beethoven?” We do not live in a world anymore where we believe that high culture would save us. That was the intellectual conceit of the first half of the Twentieth Century, that with the right kind of cultural training, the world would be more civilized. And the most civilized country in Europe - Germany - became the place of barbarity to the soundtrack of Wagner. So we do not believe in that high-low split in the same way anymore. |  |

|

|  |  |

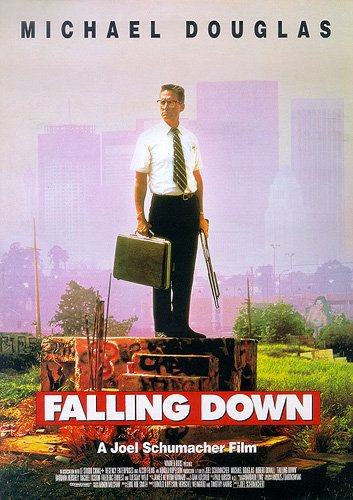

MD: Today we see a cultural return to the eighties, not only fashion and music, but also in Hollywood, where macho-heroes such as Rambo, Rocky, and John McClain from Die Hard are back. Richard Goldstein has termed this figure the “neo-macho-man”, and linked it to Bush's war in Iraq. What are your thoughts on this change in masculinity in the US public sphere after 9/11? And what effects do you think this has had on the American society? JH: I think it is a very real account. It is not just in the imagery. We can go back to the sort of stupid masculinity of Bush. A world event like the bombing of the World Trade Center on September 11 happens, and this world leader's response is this sort of cowboy rhetoric about “we're gonna root them out”, “we're gonna hunt them down”, you know. I will never forget that imagery, and sort of thinking: oh my god, this is the beginning of the end. This is unfortunately the price that we do pay for a particular kind of anti-intellectualism. This is where it does come home to roost, because in the place of a sort of reasoned and considered account asking: my goodness, what is this political situation that we have gotten ourselves into? How can we understand it? What could we do about it? How should we respond to it as a people, as a nation, or actually as a collapse of a nation? Instead you get that macho rhetoric. In the five or six years since then, not only have we seen the return of the macho-man in films, we have seen a return of all kinds of bad political behavior in general. Many people have talked about a sort of carte blanche being given to homophobes, sexists, and bigots, because the political culture of the moment is not careful, basically. So some of these school shootings you see in the US, like the Virginia Tech shootings, the media latched on to the fact that the guy was Korean-American, which may have some significance, but more importantly, this is a return to the 1980s shootings. There was a whole series of schoolboys shooting particularly girls, in Midwestern states - in these red states, Republican states. What that signals to me is that we are living in a culture where men believe they are entitled to something, and when that something does not materialize, they think someone has to pay. It is like going to the 1980s with those horrible films like Falling Down, with Michael Douglas, where the white guy looks around him and says: “Hey, where did all these immigrants come from, what happened to my Californian, Arian, sun worshiping, white people's culture”, and takes a Uzi and walks around in these neighborhoods of color blowing people away. We have returned ... no, it is not even a return; it is a new version of male entitlement that comes with an extreme expression of male violence at every outlet of the political culture. So I would go way beyond the films, and be like ... wow! |  |

|  |  |  |

|  |  |

|  | |

|  |  | MD: These days it seems legible to talk about a “remasculinization of America”, which makes a critique of the ideology of masculinity more important than ever. What role do you think queer theory and activism can have in problematizing this remasculinization? JH: I think it is queer theory and feminist theory that is needed. It is very hard to get these perspectives into public discourse. That is the problem. So you have this guy going around shooting people feeling ignored or that something was denied him, and it is hard to insert a political discourse that is not just like “this was just a one crazy dude who went off”, but getting a more considered analysis of why male rage takes this form. That is a feminist question. Why is it a feminist question? Because no other political subject probably would ask that question in that form: Why does male rage take this form? Female rage takes a form of maybe child abuse, sometimes, maybe self-mutilation, maybe anorexia, maybe schizophrenia. It does not take the form of a woman picking up a machine gun and blowing people away. It really does not. We are hard pressed to think of such an event anywhere. So it seems like one of the distinguished features of the ones performing these acts of mass slaughter is maleness. And there I would say a feminist analysis is necessary, and almost impossible to get in the public sphere, because feminism is an afterthought, or considered to be a historical artifact at this point. MD: Yes, the anti-feminist position is dominant today... JH: It is, even if almost every city seems to have a feminist art show going up, anti-feminism rules. It is really puzzling. |  | |

|  |  |

MD: I reread the last chapter of Female Masculinity yesterday where you write somewhat polemical in response to the ubiquitous cultivating of the feminine in little girls, that “it seems to me that at least early on in life, girls should avoid femininity. Perhaps femininity and its accessories should be chosen later on, like a sex toy or a hairstyle”. To a certain extent, perhaps, this could also be said about young boys, that they should avoid masculinity, at least in its normative form of idealized white-hetero-macho-hero-masculinity? JH: Well, that is true if you are thinking that the way we in general socialize kids in gendered ways is a harmful thing. Femininity just comes with a higher penalty. One should change the whole cultural discourse around masculinity. But in relationships to kids, you cannot stop gendering. It would be silly to even begin to try. But you can encourage different forms of female culture than the ones that involve make-up, hair, dolls, high heals - things that are actually not very helpful for them later on in life. At least with boys then, encourage them to play sports: that's okay; it is healthy in a country that is suffering from obesity-problems. Or getting them to think about themselves as independent - that's okay, that seems like a reasonable thing to do - or self-sufficient, or capable, or knowing about how to fix things, or taking the initiative... The things that we understand to be useful for boys to learn are useful for anyone. But the things that we think are useful for girls to learn are not useful unless your purpose, your use-value, is finding a man, who thinks that those things are useful. It is sort of a Catherine MacKinnon-type of argument, I am afraid, but the things women think are womanly are the things that men have decided are appealing. In the framework of patriarchy, femininity is necessarily a degraded discourse, and that is why I made the distinction. If you did change the way in which you socialize little girls into the project of femininity, I think masculinity would change, too. And I am not saying that you should not focus on masculinity, it is just that the impact of masculinity seems to be a little bit different. Rather than say that we should delay people's relationship to masculinity, I think we should target certain activities as a masculine problem, like bullying. So bullying is a huge problem in many schools across most of the cultures that we know of, and yet the figure of the bully is not what emerges as the pathological element. The figure that emerges as pathological is the victim of the bully - the sissy-boy who cannot stand up to the figure of the bully, or the little girl who goes crying home. But discourses of pathologicalization are not always bad. If you did have a pathologicalization of the anti-social behavior of the bully then, I do not know, maybe you could pinpoint this activity as masculine - whether a boy or a girl is participating in it - and as a version of masculinity that we do not want to encourage. In a way, it is about getting educators to think about what version of masculinity and femininity they encourage or suppress, rather then try to end gendering, which is an impossible project. MD: It is ten years since you wrote the book Female Masculinity. Do you think the understanding of female masculinity has evolved since then? JH: Yes, I do think so! I hear the term used a lot more, and it is not necessarily the impact of the book, which in the end is only really read by maybe 10 000 people, which is a lot in academic terms, but not in the world of publishing. All ideas - and this is going back to the start of our conversation - can circulate widely separate from their author if the idea has a certain kind of potential to a) be understood and b) entering into or produce new realms of common sense. And I think “female masculinity” as a term has that potential, because it does describe something that is already present in the culture, but lacked a term or explanatory system. Once you have that category you can actually refer to it now when you are thinking about tomboy-behavior, or you are thinking about adult female aggressive behavior, or whatever it might be. So ten years on, I feel that it was a pretty good term. And it was a term that I personally needed to understand myself in the relationship to the world, and it was useful for me. I do think it is a useful term, but I would also say, ten years on, that things are a little different for little girls. This has nothing to do, necessarily, with some specific event in academic culture, but has to do with certain shifting notions of what is appropriate for girls. That does seem to have changed. When you go to high schools, girls do have soccer-teams, and girls can take woodworking and metalworking and car engineering and so on. There is less of a strict sense of what is appropriate for a girl to do, and for this we should really be accrediting much more to feminism than we do. MD: Do you have any plans for projects after Dude Where's My Theory? JH: I have a couple of next projects. One is that I want to take up the topic of animation and go further with it. I actually want to see if I can do a sort of ethnography of Pixar and the animation studios in LA, both as work places as well as in terms of the kind of films they produce, and then in terms of technology of animation. So I remain interested in animation. Then, the other project is more personal. I am trying to think about my dad's biography. He was a Jewish refugee from Czechoslovakia, a kind of transport child who ended up in England. He has a kind of interesting history. His mother was deported in 1942 from Prague and died in a camp. He has a stack of letters from her, and I am trying to think about what to do with his autobiography and his letters. So those are my two very different new projects. |  |

|

|  |  |

|  |  |

|