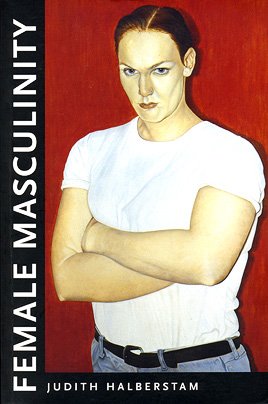

MD: I reread the last chapter of Female Masculinity yesterday where you write somewhat polemical in response to the ubiquitous cultivating of the feminine in little girls, that “it seems to me that at least early on in life, girls should avoid femininity. Perhaps femininity and its accessories should be chosen later on, like a sex toy or a hairstyle”. To a certain extent, perhaps, this could also be said about young boys, that they should avoid masculinity, at least in its normative form of idealized white-hetero-macho-hero-masculinity? JH: Well, that is true if you are thinking that the way we in general socialize kids in gendered ways is a harmful thing. Femininity just comes with a higher penalty. One should change the whole cultural discourse around masculinity. But in relationships to kids, you cannot stop gendering. It would be silly to even begin to try. But you can encourage different forms of female culture than the ones that involve make-up, hair, dolls, high heals - things that are actually not very helpful for them later on in life. At least with boys then, encourage them to play sports: that's okay; it is healthy in a country that is suffering from obesity-problems. Or getting them to think about themselves as independent - that's okay, that seems like a reasonable thing to do - or self-sufficient, or capable, or knowing about how to fix things, or taking the initiative... The things that we understand to be useful for boys to learn are useful for anyone. But the things that we think are useful for girls to learn are not useful unless your purpose, your use-value, is finding a man, who thinks that those things are useful. It is sort of a Catherine MacKinnon-type of argument, I am afraid, but the things women think are womanly are the things that men have decided are appealing. In the framework of patriarchy, femininity is necessarily a degraded discourse, and that is why I made the distinction. If you did change the way in which you socialize little girls into the project of femininity, I think masculinity would change, too. And I am not saying that you should not focus on masculinity, it is just that the impact of masculinity seems to be a little bit different. Rather than say that we should delay people's relationship to masculinity, I think we should target certain activities as a masculine problem, like bullying. So bullying is a huge problem in many schools across most of the cultures that we know of, and yet the figure of the bully is not what emerges as the pathological element. The figure that emerges as pathological is the victim of the bully - the sissy-boy who cannot stand up to the figure of the bully, or the little girl who goes crying home. But discourses of pathologicalization are not always bad. If you did have a pathologicalization of the anti-social behavior of the bully then, I do not know, maybe you could pinpoint this activity as masculine - whether a boy or a girl is participating in it - and as a version of masculinity that we do not want to encourage. In a way, it is about getting educators to think about what version of masculinity and femininity they encourage or suppress, rather then try to end gendering, which is an impossible project. MD: It is ten years since you wrote the book Female Masculinity. Do you think the understanding of female masculinity has evolved since then? JH: Yes, I do think so! I hear the term used a lot more, and it is not necessarily the impact of the book, which in the end is only really read by maybe 10 000 people, which is a lot in academic terms, but not in the world of publishing. All ideas - and this is going back to the start of our conversation - can circulate widely separate from their author if the idea has a certain kind of potential to a) be understood and b) entering into or produce new realms of common sense. And I think “female masculinity” as a term has that potential, because it does describe something that is already present in the culture, but lacked a term or explanatory system. Once you have that category you can actually refer to it now when you are thinking about tomboy-behavior, or you are thinking about adult female aggressive behavior, or whatever it might be. So ten years on, I feel that it was a pretty good term. And it was a term that I personally needed to understand myself in the relationship to the world, and it was useful for me. I do think it is a useful term, but I would also say, ten years on, that things are a little different for little girls. This has nothing to do, necessarily, with some specific event in academic culture, but has to do with certain shifting notions of what is appropriate for girls. That does seem to have changed. When you go to high schools, girls do have soccer-teams, and girls can take woodworking and metalworking and car engineering and so on. There is less of a strict sense of what is appropriate for a girl to do, and for this we should really be accrediting much more to feminism than we do. MD: Do you have any plans for projects after Dude Where's My Theory? JH: I have a couple of next projects. One is that I want to take up the topic of animation and go further with it. I actually want to see if I can do a sort of ethnography of Pixar and the animation studios in LA, both as work places as well as in terms of the kind of films they produce, and then in terms of technology of animation. So I remain interested in animation. Then, the other project is more personal. I am trying to think about my dad's biography. He was a Jewish refugee from Czechoslovakia, a kind of transport child who ended up in England. He has a kind of interesting history. His mother was deported in 1942 from Prague and died in a camp. He has a stack of letters from her, and I am trying to think about what to do with his autobiography and his letters. So those are my two very different new projects. |  |

|