| Sociological research on new social movements makes a distinction between identity- or status-based movements and instrumental movements which are focused on certain issues such as the environment. Identities play an important part also in the instrumental movements, in which they grow out of shared activities and commitment to the cause, but they are not regarded as the motivation of the activity. Bolsø’s proposal involves a transformation of a (gay) identity movement into an instrumental (queer) movement in sexual politics, with the clear aim to leave behind LGBT or any such framework: Queer is here not regarded as an issue of norm-breaking that only a given group of people would be involved in. But what are the content and the goals of the new politics? How are they defined? Bolsø does not discuss this issue, but it seems that the primary goal is still the same as in identity politics, that is, emancipation and liberation, but now it may concern anyone and everyone.[22] Could more be said about the aims of activism that is based on queer theory? |  |

![[22] In this Bolsø joins](Resources/item1a3a1b1a2.gif)

|

|  |  | In 1999, Jonathan Alexander, obviously disillusioned with queer, stating that “the queer movement is running out of steam” because of queer theory’s “non-transferability to activism”, feared that the identity politics which queer theory had denounced had crept back into the LGBT/queer movement. For Alexander, the problem with identity politics was that it did not support solidarity between the separate identity groups in the LGBT coalition. The queer perspective’s bid for solidarity between all those marginalised by the heterosexual matrix appealed to Alexander, but it had apparently failed in his view. Being the hegemonic groups within the movement, gay men and sometimes lesbians with them set interests of other groups within the LGBT coalition aside when they deemed it strategically necessary for their own purposes. Something more was needed as guideline for queer activism than queer theory’s offer of mere critique of identity politics without suggestions for alternatives. Echoing Seidman’s call for articulation of the ethical underpinnings of queer, but with reference to Foucault, Jeffrey Weeks, and Kate Bornstein, Alexander postulated that values were about to replace identity as the base of the movement. But in the end, neither could he articulate what those values might be, beyond relatively vague references to solidarity and sympathy, and a proposal to claim the concept of family values of the conservative right and to queer or adopt it to suit the alternative families (of choice) of the LGBT community.[23] The talk about the need for a discussion on the ethics of the queer perspective has later resurfaced in debates about intersectionality and the obvious power asymmetries between “queers” in different regions of the world that have become topical in the intensifying discussion on the globalisation of queer.[24] However, a more substantial and coherent discussion related to queer theory and research about values that might unite the movement is apparently still missing. |  | ![[23] Alexander, “Beyond Identity”.](Resources/item1a3a1b1a2a.gif)

|

|  |  | In conclusion, despite undeniable frictions in the activist application of queer theory, the theory has still had considerable impact on the activism within the queer movement. This influence has been supported by the fact that many of the activists have tended to be young and students. The main part of what they have taken (with varying success) out of the lecture halls and into their group meetings and out on the streets and other public places can be summarised in three points. First, there is a conviction that targeting the cultural sources of oppression constitutes a challenge to the hegemony of the heterosexual matrix at the most fundamental level. There is nothing secondary about addressing the “merely cultural” – the gestures that constitute the politics of the performative are very important indeed.[25] Second, the queer challenge of any ideas of coherent, prediscursive identities and unambiguous identity categories has translated into openness in people’s self-identifications. This has resulted in at least an effort towards increased alliance-building between diverse groups that are marginalised by the heterosexual matrix although there have been obstacles and failures in this endeavour. Third, the focus of the political analysis has been, to some extent, shifted from the problems of the minorities to the oppressive culture of heteronormativity. |  | ![[25] Mary Bernstein, “Identity](Resources/item1a3a1b1a2b.gif)

|

|  |  |

|  | |

|  |  |

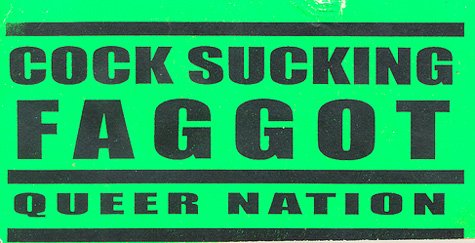

For many, queer is not queer without a radical political edge. Queer activism implies a challenging approach to sexual politics and it shuns neither controversy nor confrontation. Discussions about the political radicalism of queer activism usually revisit the model of all queer activism, the organisation Queer Nation that has been credited for the first use of queer as a political signifier in the legendary flyer with the titles “Queers Read This!” and “I Hate Straights!” on either side. Grown out of the frustration with the wilful mismanagement of the AIDS crisis by the government and with increased violent homophobia, discrimination, and hostility to add insult to injury, the embracement of anger and violent response is the sensational feature of the flyer and the early politics of Queer Nation that is remembered and quoted. Indeed, this aggression, famously expressed in the slogan “Queers Bash Back!”, was represented in the flyer as the force that would unite “queers”.[26] While a lot of what has gone under the banner of queer over the years is a far cry from this uncompromising resistance, the legacy of identification with anger and hatred and a refusal to denounce violence has not disappeared and still attracts a lot of media attention when it resurfaces. For example, in the 2008 Helsinki Pride parade it was represented by a contingent called Pink Black Block. Half-covered faces and pyrotechnic torches were visual signs that evoked associations to violent clashes in conjunction with a completely different kind of demonstrations. The group summons the energy of hate and anger also in their verbal communication with slogans such as “Queer Jihad”.[27] |  | ![[26] Rand, “A Disunited Nation](Resources/item1a3a1b1a2a1.gif)

|

|  |  |

|  | |

|  |  | In addition to the discourse of anger and (potential) violence, there are three main (somewhat less dramatic) ways in which the confrontational political radicalism of some factions of the queer movement is articulated. First, some debaters underline the importance of engagement with the abject, in public. For example in Sweden, Don Kulick has maintained that it is crucial for the queer movement to remain subversive, “uncomfortable”, and oriented towards change (which a large part of the movement and culture that today is called queer is not). To this end, queer activists and scholars alike should forefront in public debates with an open mind issues and sexual practices – such as pornography, prostitution, and promiscuity – that are perceived as controversial in a mainstream no longer shocked merely by same-sex desire. These are issues that can be, but are not necessarily, associated with gay and lesbian agendas or subcultures. In fact, Kulick regards discussion about them as a way to question the supposed unity of heterosexuality as something respectable and natural.[28] |  | ![[28] Kulick, “Inledning”.](Resources/item1a3a1b1a1a1a.gif)

|

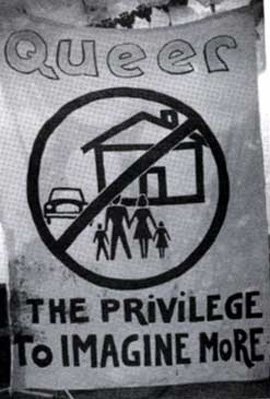

|  |  | Second, resistance to normalisation suggests a relative radicalism in comparison to more conformist approaches in non-heterosexual politics. Critique of assimilationist tendencies within the gay and lesbian movement was part and parcel of the queer approach from the beginning and still continues. However, obviously, the conditions of this opposition have changed considerably since the 1990s. Under the circumstances of the late 1980s and early 1990s in a USA plagued by AIDS and a conservative government, the gay and lesbian politics intent on respectability and lobbying was at a dead end and could well be criticised for belonging to the past, and at that time getting “us” nowhere. For a time, it may have seemed that the new queer perspective would just sweep all over it. In the past decade, however, and for instance in Scandinavia already earlier, the gay and lesbian lobby has had considerable success in promoting legislative reforms, lately including gender-neutral marital legislation in Norway and Sweden. Thus, it has regained new weight as a rival to queer politics.[29] The queer critique against normalisation and assimilation has indeed changed tone accordingly. In recent years, it has often been articulated using Lisa Duggan’s redefinition of homonormativity as a neoliberal sexual politics that “that does not contest dominant heteronormative assumptions and institutions but upholds and sustains them”.[30] Many of the critics do not oppose the concrete goals of same-sex marriage or adoption rights as such (although others are very convinced that the queer movement must not be involved in recreation of obsolete heterosexual domestic patterns in a gay environment), but express concern over the family rights campaign having become so dominant in the LGBT(I) organisations that alternative choices and lifestyles become marginalised even in the LGBT(I)/queer communities themselves. It remains an open question whether it is the normal that gets queered or the queer that gets normalised in the homosexual modification of the nuclear family, even though the latter alternative is more often presented in the literature. Finally, there is a strand of queer activism that cultivates its radicalism in its alliance patterns, that is, by cooperating with other critical and subversive movements and causes rather than privileging (LGBT) sexual politics as its primary frame of reference. For example, Gavin Brown has studied “a radical queer activism that is aligned with the anarchist and anticapitalist wings of the global justice movement” in the London group of the international Queeruption network.[31] The activities are characterised by social experimentation in organising the life and activities of the collectives. Activities take place in independent media, international networks, and temporary autonomous spaces created through squatting and groups that are kept as non-hierarchical as possible rather than in permanent organisations, and events rather than campaigns are created. In Europe, the large cities in the West of the continent are centres of this movement although the examples are widespread, including the Nordic countries. |  | ![[29] It is worth noting](Resources/item1a3a1b1a1aa.gif)

![[31] Gavin Brown, “Mutinous Eruptions:](Resources/item1a3a1b1ab.gif)

|

|  |  |

|