|

|  | |

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  | |

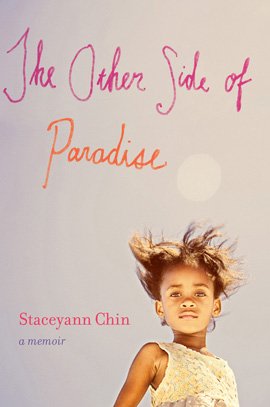

|  |  | UD: It’s really great to see you again, Staceyann! SC: It’s great to see you again too, although you have more hair now than you did last time. UD: That’s very true, I do. Maybe we’ll get to the question of hair later on… So, obviously, this is a queer literary festival and there are lots of things to talk about in terms of activism and art. Last time we talked was at a panel during Stockholm Pride four years ago with Alex Olsen, Doria Roberts and Del LaGrace Volcano. I think we’ll be touching on some of the questions that we were touching on then: how to make art and how to be an activist and an artist, and that kind of stuff. But to get us started: what have you been up to since we last saw you here in Sweden? SC: What have I been up to? Well, I’ve certainly had some girlfriends and lost them. But that seems to be a constant in my life – you know, they appear and then they disappear. Lesbians are like magicians. First we’re in love and then we’re not in love and then we’re friends and then I have to meet your current girlfriend and then you have to meet my current girlfriend and we all have to pretend we’re really all friends even though we want to stab each other in the neck with forks. UD: Is that what you do in New York? SC: No, I’ve been traveling and performing… My goal is always to articulate, not just my identity because my personal identity is no more under attack. You know, I show up and people roll out the equivalent of the queer red carpet and go running for apple juice because I said I would like something with sugar. So my personal life is very different from the life I started articulating ten or eleven years ago when I first went to America. I think now what I work hard to do is to articulate the identities that are still under the attack of racism and sexism. I represent the women of Jamaica who are unable to travel across borders to speak about their identities and their lives. I talk about people who are poor, and I suppose I represent people who might come to Sweden, who might find themselves invisible, or might find that they come up against larger things than what they are able to deal with. So I’m always writing, I’m always performing. I started on a book, that will be published next year.[1] It talks about growing up in Jamaica, about what it was like living in such a gendered identity, about being a kid with a loud mouth, about being abandoned. |  |

![[1] Staceyann Chin, The Other](Resources/attenpixel4a2.gif)

|

|  |  | To me, when I look behind me, it seems like I haven’t been up to much. So when people say “oh, you’ve been up to so much, and I saw you in this and that”, it’s kind of like I’m doing the same thing every day. One day Oprah might be interested, and another day someone in Gothenburg might be. It’s the same conversation and it doesn’t feel very different to me. I’m just plotting along and trying to do my part in a process of changing the world and making it better. UD: This new book, is it a different kind of writing? SC: It’s prose, not poetry. I haven’t put a published book of poems out because I think it takes a really long time to become a poet. And I don’t think I’m quite there yet. I’m still working on the craft of writing poems and what they might be if they were good poems. I articulate my identity within the work that I do, but I feel like some of it is still very clumsy in the craft. So hopefully, by the time that I’m forty, I’ve mastered twelve of fifteen poems to put together to a collection of work and put an ISBN-number on it. I think that we are a generation of do-it-quick and microwave and amazon.com and downloading music right away. I was raised by a woman who was sixty years old when I was born, so I’m a slow-burn kind of girl. |  | |

|  |  |

|  | |

|  |  | UD: But you have published some chapbooks. I was talking to a friend of mine the other day about this conversation, and she said “Staceyann’s work got me through a really hard break-up from my girlfriend”. So obviously, whether it’s a proper collection of poetry or not, you’re doing a lot of good work. SC: Well, I can write “my girlfriend has left me and I’m so sad here on the bathroom floor”, I’m very good at those poems because I’ve had so much practice. I’ve been fairly intimate with a lot of bathroom floors across the globe. Because there is always some woman being left or leaving me. That is always easy drama for straight people to peer into. UD: Is that not good poetry to write? SC: I don’t think that these utterances we make are invaluable. But I think that if you’re going to be a filmmaker, then you work hard at the craft of filmmaking. Not because you’re gay or black, and not because the film has to be good, but because it is important. Especially in this heteronormative white culture where our voices aren’t visible. I don’t think that people walk around and say “I haven’t had a black doctor perform surgery on me. I want the doctor who is black to perform the surgery regardless of whether he’s good or not”. It’s a very delicate conversation, the conversation that America is having around race and gender right now in the political campaign. Nobody can critique Obama because everything sounds like racism, and nobody can talk about Hillary because everything sounds like they’re being sexist. So, it’s a weird situation. When the mainstream provides space for a kind of marginalized voice, that voice becomes a voice that we are inclined to protect rather than critique. And sometimes that is problematic. UD: What constitutes good art or good poetry? SC: Of course that’s very subjective, I just can talk about what I like. You know, some people don’t need all that extra schooling. You sometimes meet a young poet who has a sensibility with words that’s just breathtaking and amazing. And you know that you should just leave that kid alone and let it find his own voice, or her own method. |  | |

|  |  |

|

UD: Slam poetry and spoken word – how did you come to choose those particular literary forms? SC: When I moved from Jamaica to US, I was a very angry young dyke who wanted to be a loud dyke. I wanted everyone to know that I was a dyke. I wanted to get the word dyke tattooed to my forehead. I wanted to be with dykes and that was the most important thing to me. I thought, “fuck my race”, “fuck being a woman”. I was a dyke. I think that’s how you are when you’re in your twenties. You’re fierce and you want to put your fist through everything, including all the vaginas you meet. I needed somewhere to put all that, and I thought that New York was the place where I could go and be this dyke. So I hit New York and then I was like, “shit, I’m black!” You know, I was black in Jamaica but so was everybody else. So when I got to the US I had to figure out where to go next. I needed a place to put all of these feelings of not belonging anywhere. Because when you’re in your twenties, belonging is the most important thing. So I found spaces in New York City – poetry café spaces – and I discovered this art where people would go up on stage shouting things like “black” and “nigger” and “pussy”. There were very few people whispering dyke. So I thought to myself “there’s no dyke up there”. So I went up there and said “dyke”. And then a whole bunch of people were like “yeah”. And then I had a career. It was just timing and caprice. |  |

|

|  |  |

|  | |

|  |  | Not all identities can get on a stage and shout “dyke”, not everybody in this room can get up on a stage and shout “dyke” and all of a sudden have a career. Which means that the very thing that provides me the career where I can talk about issues like homosexuality and safety and battered women and being an immigrant is the racist and sexist system itself. It’s very complex and fucked-up. If I wasn’t a dyke I would never be on Oprah. Or if I was a hundred pounds heavier or darker skinned. It’s this weird space where my exotic fringe identity gives me enough room to slip into the mainstream. Which is why, if your own politics are not radical enough, you become part of the heteronormative, racist construct – the umbrella under which the entire world sits. So you have to walk in there and you have to ask yourself every day: what is the thing that I need to critique today? Because it’s not always the same thing. Because sometimes being in the mainstream and saying “I’m a lesbian and I like to eat pussy” is sometimes not the most radical thing to say in that setting. UD: Indeed. So what do you do with this space that you have? You have a big audience, both in the US and internationally. What are the messages you want to get across? How do you use the space that you are given through that particular fringe identity that you were just talking about? SC: I begin with being honest. And the more people look at you, the harder it is to be honest. Because when you’ve worked out a formula it’s really easy to put on that cloak and walk out there, and you know everybody will respond to it. So I think my personal challenge is to remain honest. Sometimes it’s not always good, it’s not always interesting. But I’m a social justice activist, before I’m feminist. Before my lenses become more focused on the plight of women, before my lenses become more focused on the plight of people of color and particularly black people, or Jamaicans or people who identify LGTBQ, I must begin by saying that I work for a world in which every person can choose to live. Where it’s safe for every person to make a choice. Where the environment exists so that choice can be a real choice, as opposed to a reactive choice or a kind of compliant choice. Where you’re not gay because you think it’s the only way to be radical, or you’re not a feminist because you believe it’s the only way you can find some friends who don’t wear lipstick. Sometimes I think you have to point to the ridiculous to articulate the heart of the matter. I meet a lot of women across America who I don’t believe are gay. Who partner with women because they have had really bad experiences with men, because they hate men. I don’t know if that makes you a dyke. For me being a dyke is being someone who loves women. But if I’m an activist, then I ought to be articulating a politics that allows for you to exist in that. And that is very hard for those of us on the fringe, because sometimes what we intend to do is to walk in and flip the script, so that we become the more powerful people and the other people become the less powerful. It’s hard because sometimes I want black people to be in charge and some white people to be slaves. Sometimes I feel that way because shit is fucked up. But that’s reactive politics. That’s revenge, not social justice work. The hardest thing is the question of saving everybody at the same time. Because you see how many people that are oppressed and you see the interconnectivity of racism and sexism and you’re like, “shit! I just wanna help these motherfuckers here who are under stress. Can’t I just focus on these people, and just be a feminist and not an antiracist? Can we not talk about poverty now, because these people are being raped over here?” But the most successful revolutions that have happened throughout history are those revolutions that had groups working together, and where the people who were working against slavery were also feminists. Seeing the whole picture. I think that’s what I do, what I attempt to do. |  | |

|  |  |

|  | |

|  |  | UD: One thing that came up when we were talking beforehand was the different kinds of audiences that you speak with and read for. You mentioned that events marked as “queer” are often very white. SC: I’ve moved through so many different spaces and this word queer comes up all the time. I don’t know if it’s true for the people of color in this room, but I know that it has been consistently not been the word that we like when we are referring to ourselves as LGBT. There’s something that doesn’t feel right about the word queer for me. I use it out of necessity, because that’s the word that has been chosen. But I think that in a lot of ways people don’t recognize that different movements are at different points. Some just started, some are well on their way, and some have been going for twenty years or thirty years. Where those groups are inform what terms they use, and what are considered norm or not norm. I do not even know what to say in Jamaica to say “these people are queer”. When I get there I have to use terms that forms the vocabulary of that community. I think the use of “queer” has to do with how long the movement has been going on in America. Since Stonewall we’ve been full speed ahead, with media and everything. There’s now a large LGBQ community, where women tend to stick together, and there’s even a black female community and a Latino female community and a white female community in New York City. The larger the group is, the more segregated it becomes. Because you have a large group of people who can band together and say “ok, these are our issues”. What I’m seeing is a lack of coalition work – a lack of pulling together of resources. We get caught up in the semantics of naming things, which is why I sometimes do use the word queer because it gets the conversation moving, as opposed to us quibbling over this word. If you find out that another group uses a different word, use a different word to articulate the conversation. The conversation is what is most important. The essential thing is to articulate a dialogue. |  | |

|  |  |

|  |

|

|