|

|  |

|

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |

MD: This interest in dubious and playful propositions, reminded me of your last chapter of Between You and Me. In this text on Jasper Johns’s painting Target with Plaster Casts (1955), something happens in your style of writing. While your tone in the book is witty and sharp in general, this chapter includes fictional passages, as well as a staging of your sexual desires and projections in interpreting this work. Your reading of the empty blue compartment in Johns’s painting as an anus, while describing your own interest in male bodies and anuses, is a risky thing to do in the context of a scholarly text. This chapter is not only unexpected and fun, but it also is important in pointing out the ways in which projections of desire are central for art historical interpretations, even though this seldom is recognized or discussed. Will you continue to write experimentally in your new project? GB: I hope so. The project is not fully realized yet, and I’m currently at the stage where I’m not quite sure what form it will take. I’m heartened to hear your reception of the latter parts of Between You and Me, as it is precisely the way in which I was thinking it might work, as a kind of hyperbolization of how art history is habitually done: Taking it to the nth degree in order to really overplay it, to the point where it almost becomes impossible to take it seriously. But I hopefully didn’t play it so far that one could just simply dismiss it. I left the reader with the projections that I had staged, whilst not letting him/her be quite sure how to take them. That is very difficult to do in terms of the performativity of writing a piece of scholarship. Particularly difficult because scholarly work is perhaps the most preeminent mode of writing seriously – it is a focused form of reflective activity: You spend a lot of time doing it, researching for it, thinking about it, writing it. Theorizing is such a serious business. To some large degree I am embedded in that serious machine. After going through my education, and the projects and writing that I have done, there is a level at which I become a subject of that serious scholarly machine. The question then is, what room is there for negotiation or movement? The answer to that may reside in thinking of genres of writing other than the scholarly monograph. This new project might be better served were it to exist in some kind of difficult or tangential relationship to the more strictly defined scholarly piece of work. For instance it might turn out to be a more “creative” project, or it might involve active dialogues with some of the artists, which might take on an explicit performative dimension, as in my forthcoming collaboration with David Hoyle. |  | |

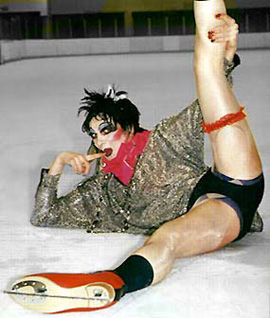

|  |  | David Hoyle may not be well known outside of the UK. But he is a really interesting contemporary queer performer based in Manchester who was formally known by his performance alter ego The Divine David. He was infamous on the queer performance circuits in London and even more broadly in the 1990s. He finally lay The Divine David persona to rest in 2000 and took a performance sabbatical for five or six years, and returned as David Hoyle performing under his own name. I have been looking at his recent shows at the Royal Vauxhall Tavern in London called Magazine, which adopt the format of the magazine in so far as each weeks show is a different issue, focusing on a different subject, whether it be war, or spirituality, or keeping fit, or whatever it might be. It is a kind of performance periodical. There are various parts that comprise it. Part of it is stand up comedy, part of it is a weekly interview – usually of somebody who is an expert on that weeks subject – but it also includes live painting, performance of so-called “abstract shapes”, which is a kind of piss-take on modern dance, and so on. There are many different components to his work. In the development of my work on David Hoyle I engage in a dialogical project with him, though is in unclear what the outcome of that may be. So the form of my project is an interesting and open question for me at the moment, and maybe to some degree that is the best thing about it. It should remain a problem that the reader has to deal with: How to take this thing? Therein resides the power of ones methodology, that it should work with the whole apparatus of scholarly research both creatively and critically, and trouble it in some productive kind of way. |  |

|

|  |  |

|

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |

MD: Your new project raises not only issues of politics within academia and contemporary culture, but also questions of ethics. Can you elaborate on your thoughts on the political and ethical aspects of rethinking seriousness? GB: To take the political first, to some large degree I’m thinking about the project as having a kind of politics in itself. Not only on a local level – as a politics of queer research – but much more broadly as it is enquiring into notions of political agency: What might be the power in embracing purportedly non-serious forms of behavior? Might there be a kind of politics to that? Obviously all of this has a direct relevance to what we think of now as the typically queer activism of the 1990s: The direct actions with the In-Your-Face and very theatrical Kiss-ins and Die-Ins, etc. Actions that were styled very much as a kind of politics that wasn’t about soliciting respectability. It wasn’t about being taken seriously as representatives of a conventional political power block or pressure group. The strategies that were utilized weren’t the protocols of some forms of equal rights politics which were about pressure groups, etc. My project kind of tracks back to that moment, and hopefully begins to mine the possibilities of what might be deemed to be non-serious forms of action, and the agency that might accrue to them. But I’m thinking about this in relation to scenes of cultural engagement, in spectatorial responses to performance and visual art practice. So it is very much a cultural project, as I’m not at present looking at any activist performances, which is not to say that I wouldn’t. At the moment it is very much on the level of cultural consumption. That is what I can say on the political. As for the ethical, on how we might conduct ourselves in relation to others and to culture – that interests me a lot. Once we begin to adopt a tangential relationship to serious culture and the modes that are proper to serious appraisal and response, it begins to open up the question of the ethics of response: How should we then respond otherwise? It opens up the potentiality of those modes of responding that have often been characterized as inappropriate and ethically dubious. It might be about laughing in the face of something that is highly grave. Or embracing the inappropriate response in the name of a perverse ethics of cultural consumption, which is about paying heed to the object, respecting it on terms other than of the serious. I use the term trashy – I’m interested in a trashy ethics. When we think about trash music, or we go to a pub where they play trash music, it signals how we hold something dear that may be important to us, without taking it seriously. Nevertheless, it still has some sort of virtue to us. There’s going to be a historical dimension of this project, which is going to be about mining the relation between what I call queer seriousness and how it emerges or is embedded with trashy culture – thinking of it in relation to, for instance, underground film by the likes of the Kuchar brothers and John Waters, or trashy TV, which brings in the mass cultural dimension. And it might also be on the level of mining the history of camp. The trashy ethics is something I am very interested in, but whether or not it is a project specifically about trash or camp I am not sure at this moment. Going back to that Ludlam quote, if I am interested in how we might think of gravity and profundity outside of serious culture, then Susan Sontag’s definition of camp is not what I am talking about. In “Notes on Camp” (1964) she defines it as a way of being trivial about the serious.[7] I am talking about it as a way of being trivial in the production of importance, of trivially entertaining the important. It sounds like a pedantic argument about terminology – about the queer production of “importance” rather than “seriousness” – but it is actually quite crucial in beginning to fine-tune what my subject is. |  | ![[4] Adam Phillips, On Flirtation, (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1994).](Resources/item1a2aa.gif)

|

|  |  |

|

|  |  |

|  |

|

|

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  | MD: Picking up on the questions on terminology, in your talk on Oreet Ashery’s performance at The Whitstable Biennial, you used a couple of terms that were new to me. In your descriptions of the spectatorial reponse to her reenactments of the surreal acts of the controversial 17th century false messiah Shabtai Zvi, you spoke not only about pathos, but bathos and quathos.[8] Could you elaborate on the meaning of these terms? GB: This has actually come out in my work on the performances of Kiki and Herb, and I have written on it in the small-scale publication The Art of Queering in Art edited by Henry Rogers.[9] What got me thinking about this was the particular ways in which some contemporary queer performances solicit pathetic responses from their audiences. On one level, we feel that we should take the emotion that is being staged seriously. But at the same time, as in the Kiki and Herb example, it moves you, while at the same time undercutting that feeling. It undercuts the emotion that you feel at the same time as you feel it. That is the bathos, the undermining of the pathos. You have the empathy and the feeling, almost at the same time as you have the rug being pulled from under you. That’s where I introduce my queer theoretical take on that, to think about neither pathos nor bathos, but quathos. This is what I call a queer emotion, that is neither one nor the other, but a rather curious intermixing of the two, where you can’t decide what it is, how to take it, or how to feel. That’s a queer emotional moment. It is almost as if the one affect of pathos bleeds into the other. A point is also that quathos is a ridiculous term that clearly has a level of playfulness or glibness to it – a bit of a gag, really. I like that. I like the idea of doing conceptual theorizing as a stand-up comic. What does it mean to do theory as a practical joke? How would one think about joking as theorizing? MD: That would make theorizing much more fun! GB: It could be, but then it can also be so bloody difficult. That’s the kind of paradoxical and almost impossible nature of the project that I have set myself. MD: This brings us back to the importance on the paradoxical in your work. In your introduction to After Criticism: New Responses to Art and Performance, you write that criticism should aim at being paradoxical, not in the sense of being contradictory, but as being against doxa. GB: Yes, and the paradoxical is that which is so against received wisdom, as it is viewed with suspicion. It is so wide of the mark of how we conventionally think within consensus – the doxa of, let’s say, scholarly work – that it is very difficult to take it seriously. An example from history might be Marx and Engels’s famous use of the camera obscura-metaphor to describe ideology. They asserted that the world appears upside down in ideology, as in the image produced in a camera obscura. In a way this seems so crazy: that the world as we conventionally know it is a distortion, an upside down inverted representation of the real world. That is really weird, and so paradoxical as to be doubtful, that we can actually take it on board. I think that’s where critical ideas come from. The power of critical ideas is that they are para-doxical. Against doxa, beside doxa, they depart from doxa. And that’s why I still think and hope people see what I’m doing as that kind of a critical project. |  | ![[8] See Gavin Butt, “Should We Take Performance Seriously?” in Oreet Ashery, Dancing with Men, (London: Live Art Development Agency, 2009).](Resources/item1a3a1b1.gif)

![[9] Gavin Butt, “How I died for Kiki and Herb” in The Art of Queering in Art, Henry Rogers (ed.), (Birmingham: Article Press, 2007), pp. 85-94](Resources/item1a3a1b1a.gif)

|

|  |  |  |  |  |

|