|

|  |

|

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  | MD: In his speech yesterday, and the following discussion on ACT UP’s twentieth anniversary march on Wall Street coming up on March 29th, Kramer discussed the urgent need for ACT UP to return to its former strength and start fighting again. There were also several people from the “old” ACT UP movement there, for instance Ann Northrop, who lead the discussion. How do you feel about this belief in ACT UP coming alive again? DC: The idea of ACT UP coming back... I don’t know. I do feel a kind of despair about the fact that there isn’t more political activism in the US, particularly about the war. As someone of the Vietnam War generation – the anti-war generation – it’s amazing to me that there isn’t more activism against the Iraq war. I suppose the explanation is that there’s no draft. I was susceptible to being drafted, to fight in Vietnam. But I could get out of the draft because I could say I was homosexual. MD: Did you do that? DC: I did. I had to “prove it” with a psychiatrist’s declaration. That’s how I escaped the draft. Other people that I knew stayed in graduate school, others left the country. It was a huge issue for my generation, because we could be forced to go to Vietnam and fight. It was the same thing that created ACT UP: middle-class people’s lives were threatened, and we became activists. Otherwise we probably wouldn’t have been. It was more than that in the anti-war movement, because we also then had the lesson of the Civil Rights Movement, which helped us to understand what a movement could do. Some of that remained in the founding of ACT UP. There were people who had extensive activist histories – especially women – and they were very smart about how to organize. For instance, some people had been involved with activist movements in the ’60 and ’70s, and they did the training for civil disobedience. But the greatness and uniqueness of ACT UP was that it was a very different kind of activist organization. Even though we learned a lot from the ’60s and the New Left organizations, we were really different in lots of ways. I wrote about that in AIDS Demo Graphics (1990). Even our graphics were different. We understood something about media that had not been understood before. I don’t know what the solution is now with regard to revivifying activism. Maybe you could do it under the name of ACT UP, but it can’t be Larry Kramer and Ann Northrop again. It actually has to be a group of people who are feeling the need to do something now. |  |

|

|  |  |

MD: Your current projects deal with art and politics in the decades before the AIDS epidemic. I was thinking about this in relation to a moving passage in the closing paragraph of Simon Watney’s book Imagine Hope – AIDS and Gay Identity (2000) where he writes: “For all of us, but especially for those of us infected, the epidemic is sadly very far from over. For now we soldier on. I’ve had my say”.[17] Watney’s “goodbye” to writing on AIDS comes after he’s been working on the epidemic for over a decade, as you yourself have done. Do you still work on AIDS at all? |  |

|

|  |  | DC: In the mid ’90 – or early ’90s even – I experienced what a lot of people involved with the AIDS epidemic did, a kind of burn out, which made it impossible to continue with that as the centre of my work. Around 1993 I began to think about gathering my work on AIDS into a book. I didn’t get around to doing that until 2000, when I finished the manuscript of Melancholia and Moralism, which included everything that I’d previously published, and also stuff that I hadn’t, like panel discussions. The idea, I suppose, was to tie up everything I’d done and call it quits. I had done that before with On the Museum’s Ruins, which was all the work that I had done in the ’80s, and when I published it in 1993 I thought I didn’t want to work on the museum anymore. But I suppose you can never really finish anything. And yet… For many years I taught courses on AIDS, and now I can’t. Because there was a time when I could approach AIDS in a sort of parochial way, in a way that had to do with people I knew, my world: New York City, gay men. That’s really what my work on AIDS is about. But that’s not any longer what AIDS essentially is about. To think responsibly about it today, you have to talk about the global situation, you have to talk about other communities that are not getting access to health care, so it’s a question of the way health care is structured in this country. It always was, of course, but still, it’s no longer the same discussion. I don’t keep up with it in the same way, and so it would have to be a whole reengagement and reeducation. When I decided to publish Melancholia and Moralism, simultaneously I was deciding to get involved with other material. |  |

|

|  |  | The most recent essay that I published – except for the one in The Eight Square that is part of this memoir project – was an essay on Yvonne Rainer and her use of music.[18] It was an essay that came out of the course that I taught on Rainer, and I really loved writing it. I’ve been interested in dance for a long time, but this is the first thing I’ve ever written about it. There are a number of things from my past that I want to work on now. I think that my Warhol book and my memoir project have political relevance. They’re meant to be about the issues that still really matter to me in queer life. But they are partly retrospective. This all sounds like a certain kind of melancholia, but I actually think there is a utility to a certain kind of melancholia; you can turn it into a kind of utility. So no, I don’t work on AIDS anymore. But at the same time, because I’m positive and I have many friends who are, it still remains a huge part of my life and the lives of many people I know. I think about it a lot, especially in relation to my younger friends, who don’t ever talk about it. It’s as if for them it doesn’t exists, but of course it does exist. So it’s something that I’m deeply aware of, and that I have to have a certain interest in, but it’s not something that I’m working on intellectually. |  |

|

|  |  |

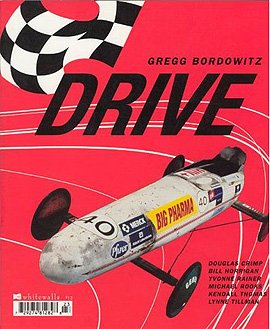

MD: In relation to this, I am interested in your thoughts on ageing... DC: ...that could be a topic for a whole discussion! (laughter) MD: I’m thinking especially of your conversation with Gregg Bordowitz in his exhibition catalogue Drive – The AIDS Crisis is Still Beginning (2002) where you touch upon the relation between the aging body and the sick body in our body-obsessed culture.[19] DC: What I can say about it is that it’s probably why I am working on the project that I’m working on. It has something to do with trying to reclaim, at least in memory, my youth, to go back to what my interests were. You think you can drop things at some point in your life, but then you realize that they still have meaning for you, but they have meaning in a different way. I have a lot of thoughts about ageing, but it’s banal stuff, I’m afraid. At the same time it’s something I try to turn into something productive. I have friends who are older like Yvonne Rainer and Leo Bersani, who are still enormously productive, so that’s the hopeful side. I’m trying to make something productive of the fact that a retrospective position feels necessary to me, because I can’t pretend that I understand or can keep up with what’s happening in the art world. There are certain things that can interest me, and I can engage with them, but I can’t have the same relation to them as I have to the artists of my generation or the next generation, the Pictures generation, that I was part of. Partly this has to do with changes in the nature of the art world. It doesn’t mean that I have to stop, but rather that I can look at things again – look at my past – and reflect on them in a different way. I think a lot about ways you console yourself, how you replace kinds of pleasures that you once had with different kinds of pleasures. My relationship to the city is different. I don’t go to bars, and I always used to go to bars. Now I see more films, I see more dance performances, hear more concerts, and go to the opera. I don’t feel any less active. If you’re a professor and a teacher, you have a relationship to your students in which you learn from them about their interests. They open worlds to you, or they open aspects of yourself to yourself that you wouldn’t otherwise think about. One of my ways of dealing with it is to be involved with people of other generations, not just stay locked into a world restricted to my own generation. But aging is a nightmare in this country, because we don’t take care of people. For me the other side of it is that I’m not somebody who cared about being in a couple. In fact, I am quite adamantly anti-couple because I don’t like the privilege of one particular kind of relationship over all my other relationships. I have so many different kinds of relationships, and I try not to hierarchize them with particular kinds of names like “the significant other”. But that also leaves me in a vulnerable situation, although I’m trying to think of it as a less vulnerable situation, in the sense that I have a system of relationships that I feel I can depend on. There’s no real solution to it. People are thinking about gay retirement communities, but that’s not a queer world for me. |  |

|

|  |  |

|  |  |

|