|

|  |

|

|  |  |

|  |  |

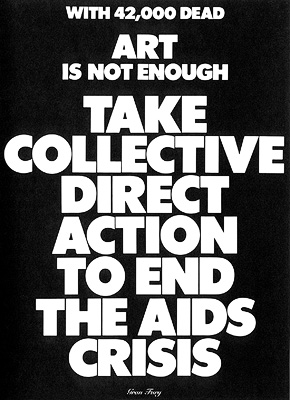

|  |  | In the process of working on it, I realized that it was important to get people who were working within the affected communities – activists who weren’t academics – to write for it. There was a woman who went under the name Scarlet Harlot, who worked on prostitutes’ rights in relation to AIDS. I met her in the movement, and I thought that it would be great to get a prostitute to write about prostitutes’ rights in an AIDS context – so I did. And I got people from the PWA Coalition, because these were the people who knew about the epidemic by dealing with it every day of their lives. I wasn’t thinking, “let’s put activists and academics together”. I was just thinking “who knows the issues?” In the end it became a strange hybrid of different kinds of voices speaking about AIDS, including people who were writing as activists, writing manifestos. It resonated with all sorts of people. Whether from the activist or the academic perspective, it was a different kind of language than they were used to reading. The activists where suddenly reading Leo Bersani, who was writing from a complex psychoanalytic notion of sexuality that was certainly not part of the activist discourse. And then were artist-activists like Gregg Bordowitz... |  | |

|  |  | MD: He has such a powerful opening line of his essay “Picture a Coalition” in the issue: “As a twenty-three-year-old faggot, I get no affirmation from my culture...”[10] His voice really feels strong in that academic context. |  |

|

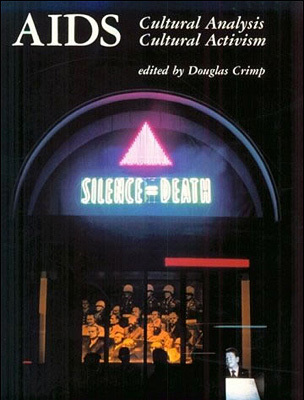

|  |  | DC: Yes. The issue was a success. It sold more copies than any other October issue prior to that time, and then we reissued it quite quickly as a book.[11] It’s still in print. It stills sells, oddly enough, because it’s really out of date now. But it’s understood as a model, I guess. You know, I was doing it blind. I just got caught up in it. I just started to go to ACT UP meetings, and then demonstrations, and I met all of these people. It became a huge part of my life while I was working on it. The issue I was editing before the one on AIDS was a special issue with Benjamin Buchloh on the Belgian artist Marcel Broodthaers. So you can see – again – the “back room/front room of Max’s” schizophrenia in my life. But it was a time of great intellectual excitement for me – and fear and panic. It was a rollercoaster emotionally. I was doing the best I could, essentially, but I also knew that what I was doing was important. I knew that I was producing something that was necessary, especially from the perspective of the art world. People were blind to the reality of what was going on, and I knew that this would get people thinking. I knew who read October, and it wasn’t people in the AIDS movement, except in so far as a lot of people in the AIDS movement were also people studying in the Whitney Program – young art world people. But in general the readers of October wouldn’t expect something like the AIDS issue. It got a lot of attention. |  |

|

|  |  |

|  | |

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |

MD: What did Rosalind Krauss and the other editors of October think about the issue? I’m wondering in relation to the fact that you left October just a couple of years later. DC: The AIDS issue is, in fact, the reason I was pushed out of October. Of course on some level my fellow editors were pleased that October got so much attention. But in the end I think it got too much attention for their taste. You know, my name was suddenly up front. I had been seen by them as the younger one going to the office and doing the day-to-day work on the journal. Even after I became a full editor, I still essentially did the job of managing editor. I did all the proof reading, I did the layout, I did everything. By then it had gotten to the point where the other editors were not as hands-on with the journal as they where when I first got involved with it, so a lot was left to me. So when I said that I wanted to do a special issue on AIDS, they said OK. They never read any of the material before it came out, and I think they probably didn’t read it at all until later, after it got so much attention. And then they didn’t really like it. For them, it wasn’t what October was about. And you can see from what they’ve done since I left what they think October is about: it’s about a retrenchment around a traditional notion of high modernism. In the 1980s, October was thought of as the journal of postmodernism. But the commitments of Krauss and Michelson and the people now connected with the journal have always been much more high modernist in their orientation. But I wouldn’t have been able to articulate that at that time. I think the fall-out felt more like it was about issues of sexuality and cultural studies. My interests are not in high culture specifically, but culture in a more hybrid sense. |  | |

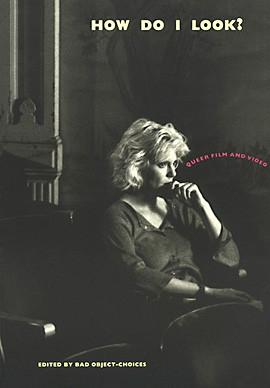

|  |  | MD: The book you co-edited with your reading group Bad Object-Choices – How do I Look? Queer Film and Video (1991) – wasn’t that initially supposed to have been an October issue? DC: Yes, that was the precipitating reason that I left. The papers of the conference that my reading group organized had been accepted by the editors for an issue of October, but when the texts came in they didn’t want to publish them. There were two texts in particular that they rejected. It’s a long and complicated story – like any divorce – but I was forced out. That was in 1990. And luckily Bay Press published the papers as a book instead.[12] MD: There seems to be a huge split in the focus of October around that time. I’m thinking, for instance, about the roundtable discussion published in 1993 on the Whitney Biennial, where Rosalind Krauss, Hal Foster, Miwon Kwon, Benjamin Buchloh and Silvia Kolbowski strongly criticize the issues of “identity politics” and “political art” that the show addressed.[13] Compared to your AIDS issue of October, well, they’re miles apart... DC: It’s a different world... MD: They don’t even mention the word AIDS in their discussion, even though this was an important backdrop for several pieces in the show. Instead they discuss “political art” in almost universal terms, without relating the show to the current social and historical context. Only Benjamin Buchloh seems to have a different angle on it all. DC: I think that there was a reaction to what I had done. The editors brought in allies whose work and interests were more narrowly focused in the direction in which they were moving. That direction was against the direction in the academy and intellectual life toward cultural studies and questions of identity and difference. This was the moment of queer theory, for example. Shortly after I left October I began teaching in the Visual and Cultural Studies Program at the University of Rochester, and I think that then things got more and more polarized. If you look at October’s issue on “Visual Culture” (Summer 1996), there’s a real retrenchment with regard to disciplinarity, whereas October had earlier been committed to interdisciplinarity, because of its commitments to poststructuralist theory, but also to not just the visual arts, but also literature, film, and a range of different subjects such as politics and psychoanalysis. But then interdisciplinarity came to seem to them something else, something that threatened their high modernist position. |  |

|

|  |  |

|  |  |

|